Article

EU Roll-out of Green Hydrogen: Ready for Take-off?

2 August 2023

Unlocking the Path to Green Hydrogen in Europe: Assessing Challenges to Deployment, EU Political Intervention, and the Access to Finance

In this article, I will delve into the status quo and path ahead for a European green hydrogen economy. It will focus on the challenges to deployment, the outlook for project finance and the EU’s political response to the American Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which was analyzed in Josh and Agathe’s recent blog post. Read on to explore this fascinating crossroads of energy policy, technology, and finance, and feel free to engage in the comments section of the original LinkedIn post.

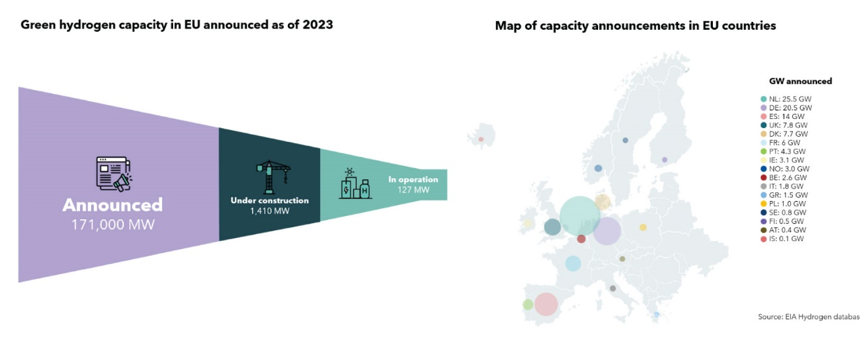

If you’re following the news, you might think that the European green hydrogen market is booming – almost every day, another project is announced. At this point, Europe’s hydrogen-related pipeline makes up 35% of the world’s announced investments, bigger than the US and China combined. However, the rate of announcements is much higher than the rate of deployment, meaning an increasing number of projects are pending Final Investment Decision (FID). What challenges to deployment are slowing down developers’ FID? How will the projects get financed? And how has recent political intervention impacted the EU’s readiness for a Green Hydrogen take-off?

Why green hydrogen production is particularly important in the EU

Europeans should be more interested in local hydrogen production than Americans and thus have a higher willingness to pay, e.g., via tax, mainly because the EU is an ‘Energy-hungry’ Union devoid of significant local hydrocarbons to cover our consumption. In 2021, the EU imported 80% of its total gas need, with domestic production halved over the last ten years, in sharp contrast to the US, which is a net exporter that increased domestic production by 51% in the same 10-year period. Furthermore, 99% of the imports the US did receive arrived through pipelines from Canada, which is arguably a more reliable trading partner than the EU’s historically biggest natural gas provider.

In the EU, it is becoming clear to governments and companies that national security is linked to energy security. The demand from existing sectors like fertilizer, cement and steel production is larger than the green hydrogen production capacity the EU can realistically build and import before 2035. The key to a mass roll-out of green hydrogen production is thus not to invent new use cases for hydrogen, such as hydrogen cars, but unlocking the existing hydrogen demand by replacing grey with green molecules.

Challenges to deployment

So, what challenges for project developers are holding back a massive roll-out of green hydrogen production? There are many challenges, such as how to transport the hydrogen at a reasonable cost from production areas to consumption hubs, long lead times on essential equipment (e.g., electrolyzers and transformers), and securing cheap electricity supply (e.g., building co-located renewable assets). However, the biggest challenge to reaching FID is signing a long-term offtake agreement with a partner willing to pay a significant premium compared to grey hydrogen.

We are still in a world where producing green hydrogen is three to four times more expensive than grey hydrogen made using natural gas. This limits the offtake feasibility for many low-margin sectors with little opportunity to pass on the cost to their customers. For example, nitrogen fertilizer production is an obvious off-taker of green hydrogen. However, we are unlikely to see many nitrogen producers signing off-take contracts with the current market setup. This is because fertilizer production is a low-margin industry, where natural gas represents 60-80% of the variable cost; thus, changing from grey to green hydrogen will significantly increase the price of fertilizers, which farmers have little opportunity to pass on to end customers. However, similar to organic food, signaling and labeling of products in supermarkets might allow farmers to pass on a green premium on foods produced using green fertilizer, thus unlocking a massive demand for green hydrogen. Another promising way forward is for politicians to decide on a minimum percentage of green hydrogen required for all EU fertilizer producers, starting very low and increasing steadily – a solution which might also be used in other industries, such as steel production.

As a rule of thumb, we will see that off-takers of green hydrogen will have one or several of the following characteristics: (1) high-profit margins, (2) ability to pass on the green premium to customers, and (3) pressure to replace grey by green hydrogen from politicians, shareholders, and end consumers.

The difficulty of signing long-term offtake agreements between producers and consumers of green hydrogen is essentially a chicken-and-egg problem, where the off-takers have little to gain from being first-movers. Mainly because costs are expected to decrease as the technology moves out the learning curve resulting in lower capex, opex, and improved plant efficiency. However, we need projects for manufacturers, sub-suppliers, and developers to improve the technologies and processes. This is where government intervention has a major responsibility: getting started with deployment, similar to wind energy in Denmark and solar PV in Germany, where governments implemented R&D and industrial policies and utilized Feed-in Tariff systems to subsidize and de-risk the economics of projects.

Political intervention

Thankfully European politicians realize that government intervention will be needed to reach market competitiveness at the speed required to reach any climate targets. The invasion of Ukraine and the IRA bill have created the urgency and support needed for political action, which we now see through various policies and institutions designed to support hydrogen recently announced, most notably:

- H2 Global (2021): H2 Global acts as a market maker using a double-blind auction structure to sign 10-year offtake agreements with producers and 1-year supply agreements with major consumers, currently H2 Global is funded by Germany (M 900 EUR).

- RepowerEU (May 2022): Broad road-map to ending EU reliance on Russian fossil fuels.

- CBAM (May 2022): The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will protect local H2 production by ensuring that imports will pay a carbon price equivalent to the EU ETS.

- The Delegated Acts (February 2023): Established clear definitions and methodologies for certifying green hydrogen to ensure that both EU and non-EU produced green hydrogen meet the same low-carbon requirements.

- European Hydrogen Bank (March 2023): A funding vehicle for providing revenue support to producers through 10-year fixed green premium subsidies, the first pilot auction with M 800 EUR funding is expected to be held in Q4 2024.

- TCTF (March 2023): The Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework for State Aid loosen the state aid restriction on hydrogen production.

Creating policies for scaling hydrogen can be seen as a balancing trade-off between being overly bureaucratic and too lax, between carefully designed incentives and speed of implementation. The EU’s complex bundle of policies and support aims to provide support and risk transfer through selective tender processes. The supporting institutions have different grant application processes, which take time but ensure projects live up to a certain standard and prioritize better projects. On the other side of the Atlantic, the IRA is less complex, and the 10-year production tax credit of 3 USD/kgH2 is accessible to all projects which live up to a list of requirements. In comparison, the political framework of the EU seems to be a cheaper road for the government to scale hydrogen, whereas the IRA is likely to get projects off the ground quicker.

Access to project finance

Due to political intervention, European hydrogen projects are in a much better place now than two years ago. Unlocking project finance for hydrogen developers has the potential to act as a catalyst for the speed of deployment in the industry. However, attracting project finance is very challenging as the structures to de-risk project cash flows are still not widely available. Therefore, the first project finance transactions in the green hydrogen industry will require developers, off-takers, banks, and financial advisors to think creatively about each project’s financing and structuring.

Getting banks comfortable with a repeatable structure to finance green hydrogen production plants would speed up the FID on a significant amount of green hydrogen projects, thus unlocking the private capital and capabilities of many more developers. In contrast to today where most projects reaching FID are financed on balance sheets by incumbent oil and gas majors. However, unlocking project finance may require support and guarantees from Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) and multilateral such as EIB to share risk with commercial banks in the first green hydrogen projects, similar to what was done for the first wind and solar PV projects.

The particular risks that attract the attention of debt providers are the price-risk of the hydrogen, counterparty risk, green electricity availability risk, and operational risk. The structures capable of mitigating these risks include long-term renewable PPAs, bankable off-take agreements with credit-worthy counterparties, and performance guarantees for equipment. Furthermore, in projects that include both an electrolyser and a Renewable Energy Source (RES), a major headache is the interface risk during construction between electrolyser and RES, since either asset is useless without the other. Structures such as an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) full-wrap or a wrap-around guarantee would specify a single point of responsibility, consequently mitigating the project’s interface risk. However, despite being a potential bonus for banks, full-wrap guarantees will likely not be a requirement, analogous to offshore wind construction where the EPC for the Balance of Plant and Turbines are still separate.

For EU developers to secure project finance, there is no room for red flags, and they will have to combine bankable EPC contracts with cheap access to green electricity projects and government subsidies. Critical tasks are transparent negotiations and partnerships with off-takers while securing subsidies from institutions such as the European Hydrogen Bank, Next Generation EU recovery fund, and H2 Global. Despite these support mechanisms being limited to ten years, they do provide a level of certainty for curious banks looking to gain a foothold and experience in this growing industry.

Conclusion

It is evident that there are critical challenges for developers, the main one being signing long-term off-take agreements, particularly due to the cost gap between grey and green hydrogen. However, that gap will decrease as the technology develops and has already been narrowed by political intervention driven by a strong will to reduce Europe’s energy dependence. The EU’s political intervention using grants and CfD tenders provides support, and risk transfer seems a cost-efficient way to support deployment. Looking ahead, the successful developers will be those that manage to secure solid off-take agreements and grants, allowing them to structure projects convincingly enough for institutions to provide loans and resulting in strong economics that enable decision-makers to take Final Investment Decisions.